“There is a mental health crisis in our classrooms. Children and young people today face a huge range of pressures, from exam stress to cyberbullying to finding a job when they finish education, and all the evidence suggests that the situation is getting worse.” (Sarah Brennan, Chief Executive of YoungMinds)

According to a recent survey commissioned by Young Minds, the emotional wellbeing and mental health charity for young people, 82% of teachers agree that the focus on exams has become disproportionate to the overall wellbeing of students, whilst 70% think that the government should rebalance the education system to focus more on student wellbeing. (Young Minds Website)

It’s a stark reminder that our instinct to help children navigate a path to ‘success’ should constantly be tempered with a focus on their emotional wellbeing. And that Generation X/Y’s definition of success – typically understood as formal academic and sporting achievement – may not align with the new opportunities and threats facing Generation Z.

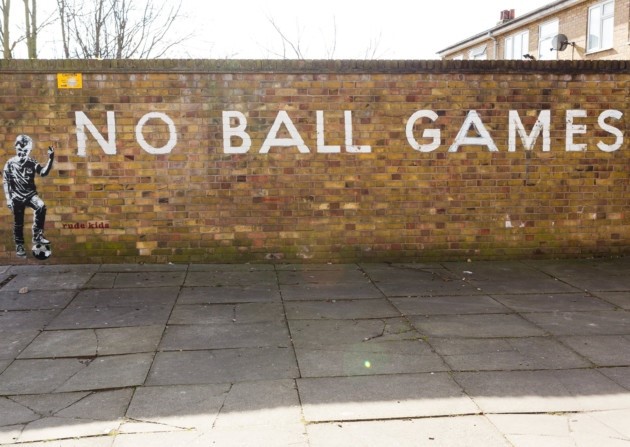

The Slow Education movement paints a vision of schools which stretch children by finding the “optimal challenge for each and every student”. It advocates ‘“developing children’s life skills and disposition” and opposes “a system that marches cohorts through examinations on the basis of their date of birth (and) risks dehumanising each and every (student).”(The Telegraph). The contrast with the re-emergence of the grammar school agenda could not be more pronounced.

As a parent, the slow education concept is appealing. My shoulders drop a good three inches from the sense of relief it offers. But putting it into practice is a bit more of a challenge. Thanks to media, peer and self-inflicted pressure, my 5-year-old son’s calendar is jam packed with playdates, nightly homework, weekend project work, scheduled downtime, minimised screen time and an exhaustive list of organised sports – taekwondo, tennis, swimming, gymnastics, cycling, football. I’m tired just listing it.

“Whatever happened to just playing” my husband asks “Oh we do that on Saturday between 2 and 4pm” I retort. So typical, so middle class.

When Sport England launched its Towards an Active Nation strategy in late 2015, it announced that for the first time it would fund programmes for 5-13 year olds, particularly targeting those socio-demographic groups currently underrepresented in sports participation.

The Families Fund is the first of these programmes and will receive £10m of investment in Phase 1. The programmes will support projects working with families with children aged 5-15. Funding will target low income families, families living in areas of high deprivation and families where children are active for less than 60 minutes a day. The fund is informed by the idea that parents and caregivers shape children’s attitudes to sport and physical activity, arguing that they:

- Provide support and encouragement – but they can also add pressure

- Share their own sport and physical activity passions – but they can also share their fears

- Facilitate access to various opportunities to be active – but they can also limit options

- Model active behaviour by taking part with children – but can also model sedentary behaviour.

Sport England suggest that funded projects should ‘“ensure experiences are fun, enjoyable and deliver value for the children and their wider family”.

Fun, enjoyment, play. These may not be words we associate with our own sporting experiences as the idea of winning is inherent to sport and we can’t all win all the time. But perhaps these are the missing pieces of the puzzle both in the classroom and on the playing field.

Giving children the room to fail, the space to try out new things, to make mistakes and learn, offers an important counter to the highly-pressurised school and extra curricula environments which more typically emphasise achievement, success and results. By focusing on family-centred activities, designed to build confidence and and togetherness rather than foster competition Sport England has the right idea.

Whether the investment will result in more active and resilient, happier and healthier, children, particularly in under-represented groups, remains to be seen and rigorous measurement of intended and unintended outcomes will be important… but it certainly won’t hurt anybody’s kids to let them play a little more!